By Taxpayer Association of Oregon Foundation

Multnomah County filed a $250 million lawsuit in August against drug companies, distributors, and doctors. The county alleges a conspiracy to hide the danger of prescription pain pills in order to promote the widespread, long-term and lucrative use of their opioid products. Last week, Governor Kate Brown’s task force to combat opioid abuse and dependency and held its first meeting.

The county charges that according to state and federal reports, Oregon currently has the highest rate of opiate abuse among people under age 25 in the United States. More than half of the drug overdose deaths in Oregon are related to prescription opioids such as OxyContin and Vicodin. Between 2000 and 2013 there were 2,226 deaths in Oregon due to prescription opioid drug overdose.

But government health-care programs—Medicaid, Medicare, and the Veterans Administration—are among the biggest suppliers of prescription painkillers. The county should look in to how Oregon’s Medicaid program may be fostering opiate abuse and addiction.

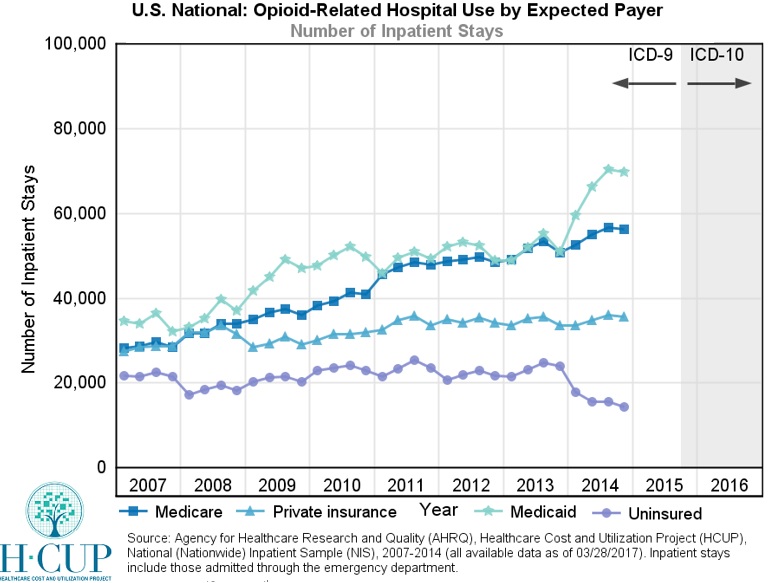

According to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the number of opioid-related inpatient hospital stays nationwide (among states submitting data) that were paid for by Medicaid increased by 42 percent between the fourth quarters of 2012 and 2014. Patient stays covered by private insurance increased 4 percent during this period.

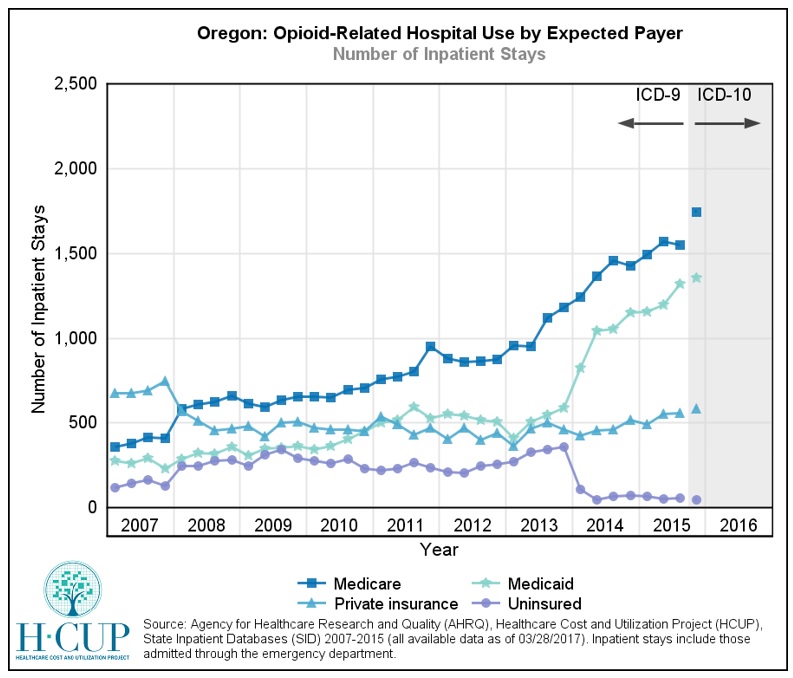

In Oregon, opioid-related inpatient hospital stays paid for by Medicaid increased 130 percent over the same period, nearly five times greater than the increase in Medicaid enrollment. Patient stays covered by private insurance increased 11 percent during this period.

Opioid-related inpatient hospital stays by the uninsured dropped in Oregon, from 250 in the fourth quarter of 2012 to 50 in the fourth quarter of 2015. But those numbers are swamped by the hospital stays paid for by Medicaid, from 500 in the last quarter of 2012 to 1,350 in the last quarter of 2015. This points to an increase in opioid use among Oregon’s low-income population.

The Wall Street Journal reports Medicaid patients may be more likely to be prescribed opioids—twice as likely, according to two studies, as privately insured individuals. A recent study by Express Scripts Holding found that about a quarter of Medicaid patients were prescribed an opioid in 2015.

Oregon has a database to identify patients at risk for abuse based on the number of prescriptions they fill and pharmacies they visit. However providers—especially in emergency rooms where many Medicaid patients seek treatment—don’t have time to check the databases, examine patients for abuse, perform follow-up consultations, or consider alternative non-addictive medications and therapies.

These problems have worsened with Medicaid expansion in Oregon. Many primary-care providers won’t see Medicaid patients because of the low reimbursement rates, so Medicaid patients turn to emergency rooms as the provider of last resort. During the long waits to see a specialist, many Medicaid beneficiaries suffering from pain are handed opiates as the stop gap while they sit on the waiting list.

Before Multnomah County and other jump on the litigation bandwagon, they should review the role Medicaid expansion has played in the overuse and abuse of prescription opioids.